Chapter 48 Appendix C: Cell Biology Topic

Background For This Sample Topic

All cells need to sense and respond to their internal and external environment. Diverse physical and chemical stimuli from outside of a cell are converted into signals that a cell can respond to through a process we call signal transduction. Signaling begins when a stimulus first appears, and usually follows 4 specific steps.

- The external or internal stimulus binds to or changes the molecular shape of a receptor or other protein that acts as a sensor for the stimulus.

- The shape change of the receptor or other molecules activated during early steps of a signaling pathway causes formation or release of a second messenger, which is a molecule or ion inside the cell that actually triggers the response pathway.

- The second messenger binds to an effector inside of the cell. The effector is what triggers the cell to actually change its behavior and respond to the initial stimulus.

- At some point the signaling pathway resets back to starting conditions, and is ready to respond to another signal.

There are many different types of signaling pathways. Most of these pathways can be arranged into families where the type of receptor, second messenger, and general mechanism of the effector are the same. These are examples of common signaling types; all of them occur in the model organism for this topic:

G-protein coupled receptors. Extracellular events that stimulate this pathway activate a membrane-bound receptor that in turn activates a G-protein complex containing 3 different subunits (a heterotrimer). The activated receptor makes the alpha-subunit leave the complex and migrate towards an effector enzyme, that is also in or near the plasma membrane. It stimulates the effector enzyme to produce one or more small molecules that act as the second messengers. The second messengers diffuse around inside the cell, activating other enzymes, transcription factors, channel proteins, etc.

There are two major sub-types of G-protein coupled receptor pathways.

- The first sub-type creates cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) as a second messenger. cAMP turns on protein kinase A, which regulates many systems.

- The second sub-type creates inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG) as second messengers. IP3 makes a cell release intracellular calcium ions from the ER that turn on rapid cell responses. At the same time, DAG turns on protein kinase C, which activates nuclear genes and other long-term responses.

Ion channel coupled receptors. Many signaling pathways begin with receptors that open ion channels in the cell’s plasma membrane. Ions diffuse in or out, triggering a cell response. Na+, K+, Ca+2, Cl-, and H+ ion channels are then ones that are used most often for signaling.

Kinase coupled receptors. Receptors in this group bind molecules like growth factors outside the cell, which activates a protein kinase in the receptor. The kinase phosphorylates intracellular proteins that act as the second messengers. This is an extremely complex family, with many different sub-categories.

The more complex an organism is overall, the more complex its signaling pathways tend to be. For instance, human cells have hundreds of different surface receptors regulating their activities. Yet even unicellular organisms have multiple kinds of surface receptors. Baker’s yeast does not have as many different kinds of receptors as our cells do, but they do have the same types, and respond in very complex ways just like our cells do.

Studying signaling can be hard because we cannot see events happening at the single-cell and molecular level. Fortunately there is a model organism that we can observe directly that behaves just like a single cell: the scrambled egg slime mold, Physarum polycephalum.

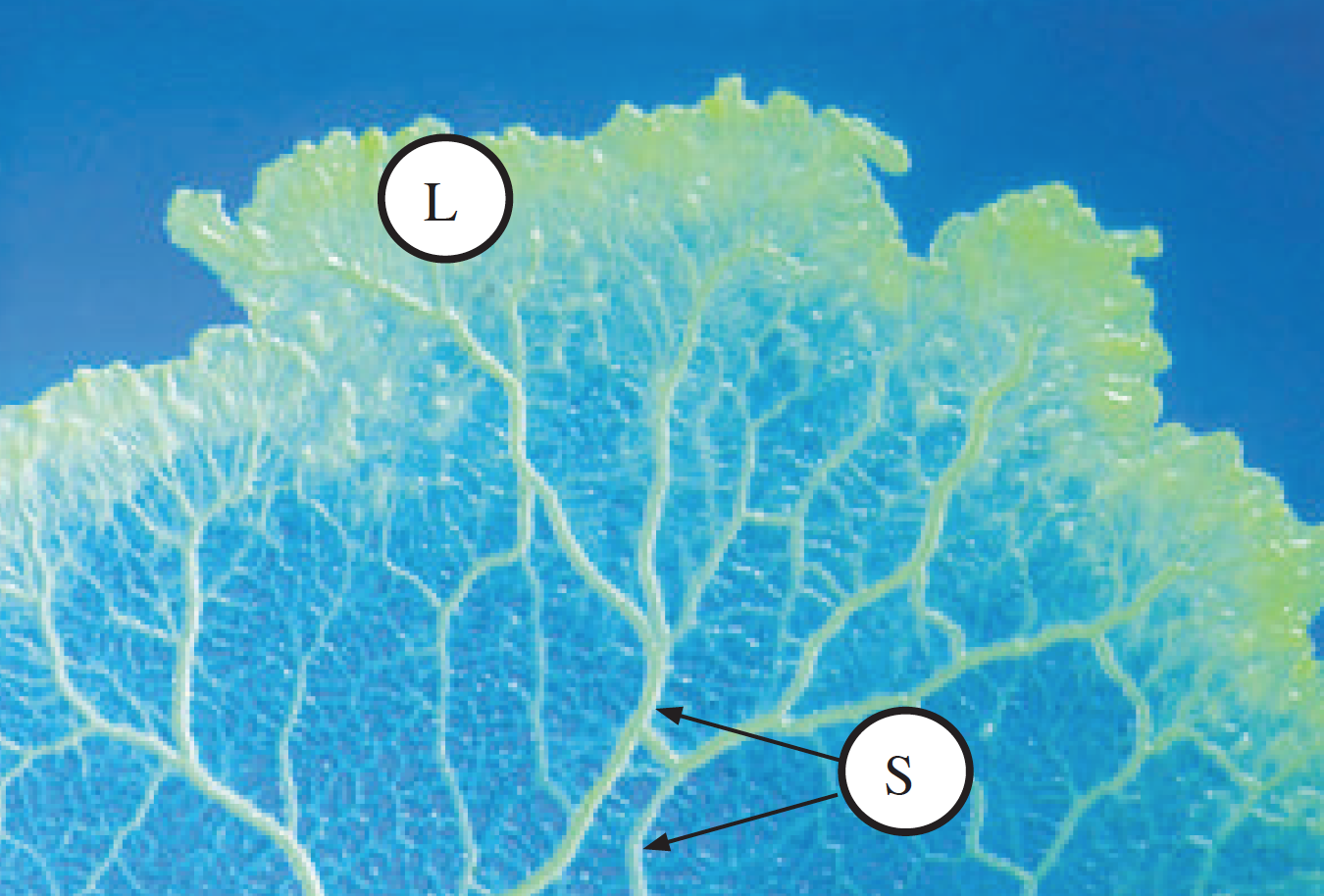

Figure 1. Photograph of the actively growing stage of Physarum polycephalum (~10X mag.). “L” marks the thicker, flat leading edge where the organism is searching for bacteria and other food. “S” marks the growth strands. At higher power, you can watch particles in the cytoplasm within these strands moving bidirectionally, switching directions at 10-30 second intervals.

Physarum is a multinucleate syncitium, meaning it contains multiple nuclei within a single plasma membrane. It has several behaviors that we can measure fairly easily:

- Phototaxis (both negative and positive, depending on growth state)

- Chemotaxis (negative or positive depending on the chemical)

- Gravitaxis (generally downward)

- Cytoplasmic streaming (bi-directional flow of intracellular fluid through long thin growth strands)

Physarum controls its behaviors using the same signaling pathways that our cells do. The difference is in what they do in response to a signaling pathway. Physarum might crawl towards the source of a chemical signal that is activating the cAMP-dependent G protein coupled receptor path, while our liver cells might make new proteins in response to activation of that same cAMP-mediated path.

Informal Starting Questions & Observations

- Why does Physarum grow away from light during some parts of its life cycle, but grow towards light at other times? How does that help it survive?

- What chemical signals could injure Physarum? Are these the chemicals that cause negative chemotaxis?

- What is the food source for Physarum? What molecules in the food source could Physarum be sensing? Do these chemicals cause positive chemotaxis?

- This is the informal question that the demonstration study explores.

- How does Physarum know which way is down? Why grow or move in that direction?

- Does cytoplasmic streaming move in both directions (towards and away from the growing edge) for the same amount of time? Does streaming rate or direction change when signaling says:

- there is food available?

- there is a toxic substance in one location?

- there is another mass of Physarum nearby?

- What would happen to its normal behaviors if the mechanism that shuts off signaling were blocked?

- The four sample reports explore this question;, specifically, how does blocking cAMP phosphodiesterase (the enzyme that shuts off cAMP signaling) affect food chemotaxis?)

Potential Testable Research Questions

Initial observations:

- It is reasonable to assume that Physarum is positively phototactic for food.

- I will need either a citable source for this information, a prior experiment that I did to show it, or to include it as a control experiment in THIS study.

- The primary food source for Physarum in nature is decaying plant material. In the lab, it is grown on plates of 2% agar in water, with either:

- a few partially cooked oatmeal flakes, or

- dextrose and some water from cooked potatoes added (this mix is called PDA).

- I will need a citable source for this information.

- What molecules in the food source could Physarum be sensing?

- Proteins or amino acids. Present in rotting plants, but neither oats nor potatoes have much protein in them.

- Lipids. Same reasoning as for proteins.

- Nucleic acids. Oats and decaying plant matter will contain DNA, but water from cooked potatoes probably does not.

- Starch. Both oats and potatoes have a lot of starch. I can only speculate on how much is present in decaying plant matter.

- Sugar. Oats do not have much simple sugar, but PDA has dextrose added. Decaying plant matter might have it.

- This argument would be stronger argument if I could back it with a citation and specific numbers.

- Out of all of the molecules that could originate from food, I think glucose/dextrose is the most likely one to be positively chemotactic because:

- Glucose is a small molecule that can diffuse easily.

- Starch is a bigger molecule and so less likely to diffuse than glucose.

- Lipids and proteins will diffuse poorly through the environment.

- Human cells sense glucose using receptors that signal through GPCRs and cAMP. I predict that Physarum senses glucose using the same pathway.

- I need a citation to back up this statement about how human cells sense glucose.

Testable hypotheses:

- If glucose is the positive chemo-attractant from food, then Physarum should move towards sources of glucose. Based on this I would predict:

- If Physarum is placed on a plain water agar plate between two food sources with different amounts of glucose, it will migrate first towards the food source with more glucose.

- Once glucose is depleted from the first food source, Physarum will migrate to the food source with less glucose.

- When the second food source is depleted, Physarum will migrate randomly in all directions.

- If the presence of glucose is sensed by a glucose receptor connected to GPCRs and cAMP, then:

- Blocking cAMP synthesis should prevent the behavior described above from happening.

Experimental Methods

- Seven days prior to starting the experiment, fresh stock cultures of actively growing Physarum were started by cutting 3, 1-cm square blocks of plasmodium from the leading edge of a stock culture.

- Each block was transferred to the center of a 100 mm petri plate containing 2% agar in water medium. Blocks were placed face down so the plasmodium was in direct contact with the new plate.

- Five to six flakes of uncooked rolled oats were scattered onto the plates to provide food. Plates were fed a second time with another 3-4 flakes of oats 4 days after setting up the plates.

- On the day of the experiment, all 3 stock cultures were checked for mold or bacterial contamination. Only healthy plasmodium without contamination was used for the experiment.

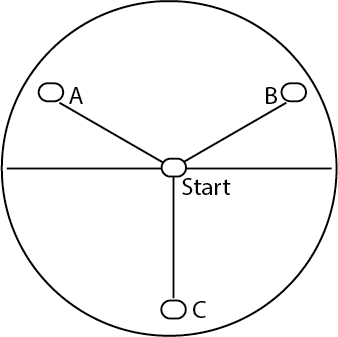

- Nine experimental plates were made using 2% agar in water plates. A line dividing the plate in half was drawn on the back of the plate, and a dot placed at the middle of the plate. This was the starting point.

- Three more dots were placed in an equilateral triangle, 40 mm from the center point, and marked A, B, and C.

Figure 2. Markings made on a 2% agar water plate for this assay.

- Three plates were pre-treated by adding 5 mL of 10 mM curcumin in sterile water to the plates. This was allowed to soak in for 10 minutes, then the plates were thoroughly drained.

- Chemoattractant plates were provided by the lab instructor. These contained either:

- No added chemical in 2% agar water.

- 0.5% glucose in 2% agar water.

- 2.0% glucose in 25 agar water.

- Test plates were set up by placing 1 cm square blocks of agar from the chemoattractant plates on top of the dots marked A-C, as follows:

| Plates | Test Group | Point A | Point B | Point C (control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-3 | No cAMP blocker, no chemoattractant | water agar | water agar | water agar |

| 4-6 | No cAMP blocker, two levels of chemoattractant | 0.5% glucose | 2% glucose | water agar |

| 7-9 | Plus cAMP blocker, two levels of chemoattractant | 0.5% glucose | 2% glucose | water agar |

- To start the assay, 1 cm squares of the leading edge of the Physarum plasmodium were placed on the starting point dot at the middle of each of the 9 plates.

- Plates were placed in a shallow tray with wet paper towels to maintain humidity, then put in a dark cabinet.

- Plates were removed and migration distances and directions measured and recorded after 24 hours, then again at 48 hours.

Sample Dataset

| Treatment | Plate # | Observations | Distance, Direction of Migration, 24 hr | 48 hr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Plate 1 | Did not seem to migrate | none | none |

| Plate 2 | Migrated randomly | 13 mm toward C | Switched; now 5 mm toward A | |

| Plate 3 | Did not seem to migrate | 3 mm toward B | 4 mm toward B | |

| Glucose | Plate 4 | Mold on this plate | 17 mm towards B | 22 mm towards B |

| Plate 5 | Heading for B | 27 mm | 40 mm (on B block) | |

| Plate 6 | Heading for B | 31 mm | 40 mm (on B block) | |

| Plus curcumin | Plate 7 | No migration | none | none |

| Plate 8 | No migration | none | none | |

| Plate 9 | Starting Physarum looks dead | none | none |

Notes For Instructors

This experimental setup is not particularly difficult for students to understand, but the sample data will be more challenging. We used this assay for many years until the course was retired. Students routinely struggled with this experiment because:

- Physarum does not always behave as expected; replicates of the same treatment may show different outcomes.

- There is no obvious way to summarize and analyze the results statistically.

Despite these limitations we kept this lab module because our students needed some experience working through complex, messy datasets. We also wanted students to begin learning how to deal with ambiguity. Other instructors may prefer to give students a more straightforward demo dataset. If so, replace the data for Plates 7-9 (+cAMP inhibitor) with random movements of 10-15 mm towards the A, B, and C points.

If students choose to compare the migration distance traveled, summarized data can be statistically tested using a t-test of mean distances for each treatment group. Alternatively students can choose to compare the direction that Physarum migrates using a Chi-square test. For the Chi-square test, the expected ratio would be 1/3 moving towards Point A, 1/3 moving towards Point B, and 1/3 moving towards Point C.